On a hot August morning, in one of Willmar’s oldest neighborhoods, stucco bungalows, ramblers and an American Foursquare here and there stand under the shade of massive trees, set close together, bordered by sidewalks. It’s a charming scene, at first glance, yet many of these homes clearly need repair.

“It’s the oldest housing stock in town,” said Jill Bengtson, the executive director of the Kandiyohi County Housing and Redevelopment Authority. Many of the homes are owned by low-income residents or retirees.

“Often, if you have people that have lived there a long time,” Bengtson added, “they are likely elderly; maybe their budgets aren’t focused on fixing their house. It becomes harder and harder to maintain that old big house.”

An aging core

Many Greater Minnesota towns are dealing with a similar question: how to make better use of an inner core of aging houses that are often too expensive for owners to fix or lacking in the big yards and amenities favored by young home buyers. It’s an especially important issue these days as employers are looking for workers in many small towns with limited housing options.

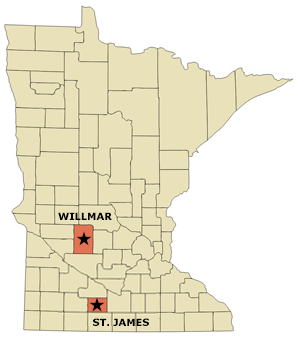

Older neighborhoods like this one – known, simply, as the Northside in this town of about 20,000 people in west-central Minnesota – would seem like good places for workers or young families to find homes, but time and demographic change have left many of them in poor condition.

In a tour of the neighborhood, Bengtson and Dale Slagter, the county’s housing rehabilitation manager, stopped along Lake Avenue Northwest as children played at a nearby park. Some people bought homes here because it was cheaper to buy than to rent, they said – but then deferred the maintenance that has now caught up with them.

“We are just scratching the surface of what’s needed in terms of rehab,” Slagter said. “There is a lot of need out here.”

For 13 homeowners on the Northside, some help is on the way.

Over the next few years, they will be able to fix up their houses with funding from the Small Cities Development Program, which is run by the state Department of Employment and Economic Development. Much of the money, distributed in the form of loans administered by the county HRA, will help to pay for new heating systems now that the city has closed a hot-water district heat program that served the neighborhood. The city’s Public Utilities Commission and a local nonprofit are also providing some funding.

(Funds for the Small Cities Development Program come from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. Some of the money will also be used to fix up rental units in Willmar as well as some commercial buildings in the city’s aging downtown core).

Six years ago, the county used $1 million from the program to help 27 homeowners in Willmar and nearby Raymond fix up their homes.

“I think we have done a pretty good job of staying on top of it,” Bengtson said, referring to housing maintenance needs across the city. “You can tell in other towns that haven’t.”

Essential upgrades

In July, the Department of Employment and Economic Development announced that 35 cities in Greater Minnesota will share about $19 million for fixes to homes, apartment buildings and businesses. To qualify for funding, projects must meet one of three objectives, according to the agency: help people of low or moderate incomes; eliminate slum or blighted conditions; or eliminate threats to public health or safety.

Willmar will be getting the largest amount of money among the 35 cities – about $1.2 million. Other cities include Brainerd ($638,000); Caledonia ($825,000); Emily ($229,000); Lake City ($809,000); Raymond ($437,000); Windom ($419,000); and Warroad ($600,000). The complete list can be found here. (Cities with fewer than 50,000 residents in counties with fewer than 200,000 residents are eligible for funding from the program).

Jill Bengtson, the executive director of the Kandiyohi County Housing and Redevelopment Authority, and Dale Slagter, the county’s housing rehabilitation manager, visit in Willmar’s Northside neighborhood.

Jill Bengtson, the executive director of the Kandiyohi County Housing and Redevelopment Authority, and Dale Slagter, the county’s housing rehabilitation manager, visit in Willmar’s Northside neighborhood.

To get a sense of the need on the Northside, county HRA officials surveyed low- and moderate-income homeowners in the neighborhood and will now sort through 43 applications for the funding. The average amount of the loans – which are interest-free, as well as deferred for families who remain in their homes for a decade after the repairs are made – will be about $15,000, according to the county.

The money is intended for essential upgrades, such as heaters, shingles and insulation – not aesthetic improvements like fences or extras like air conditioning. In Willmar, homeowners who are chosen for the funds must receive competitive bids for their home projects through local developers.

A housing crunch

Maintaining an aging housing stock, of course, is just one way that cities are responding to housing needs in rural Minnesota.

In recent years, for instance, some businesses have begun investing in housing for their own workers, such as this Jackson company. Nonprofit builders like Habitat for Humanity, meanwhile, regularly rehabilitate older homes or build new ones in small towns, albeit on a small scale. Market-based construction, of course, is a constant; builders in Willmar, for instance, are currently working on about a dozen single-family homes.

The Center for Rural Policy and Development, a think tank based in Mankato, has been studying the housing issue as part of a greater effort to understand the challenges facing small towns.

In a report issued earlier this year, the center found two main reasons for a housing crunch that has developed in some rural areas: increasing construction costs that are pricing buyers of modest means out of the market – or making rehab projects costly – and the high percentage of elderly people who remain in their homes, creating bottlenecks and leaving behind homes that need significant repair.

Kelly Asche, a research associate for the center who wrote the report, also noted in an interview with MinnPost that construction costs have outpaced wages in the past two decades or so, making the possibility of building new homes, or fixing old ones, less likely for many workers.

The Southwest Minnesota Housing Partnership, a nonprofit based in Mankato and Slayton, has been involved in affordable housing initiatives for more than two decades, including rehabilitation projects and maintenance classes for new immigrants.

Chief Executive Officer Rick Goodemann said the agency’s work has become particularly difficult in recent years. Before 2008, he said, the agency was building 40 to 60 houses each year. Now it builds fewer than 10. A home the agency could build for about $125,000 in the early 2000s now costs nearly twice that. Even rehab projects have become too costly. “We can’t make the numbers work, and we can’t do investments in homes,” he said.

Consequently, the agency has begun to focus more of its work on the maintenance and development of rental housing (including 56 apartment units in Willmar that are slated to be rehabilitated with help from the Small Cities Development Program).

Goodemann is a member of the governor’s task force on housing, which is charged with developing solutions to the housing crunch. The panel was slated to make some recommendations by the end of August.

Immigrants helping to stabilize neighborhoods

The Northside is home to many of the Hispanic and Somali families that have moved to Willmar, making it one of the most ethnically diverse cities in Minnesota. About 30 percent of the city’s residents are of Hispanic or Somali descent, according to U.S. Census estimates – a major change from three decades ago, when the town was largely homogeneous.

Besides the older homes that are attractive to low- and moderate-income residents, the neighborhood has many rental units. That’s due, in part, to foreclosed homes that were bought by investors after the 2008 housing crash, said Bruce Peterson, the city’s director of planning and development.

The city distributes a multilanguage brochure to homeowners that provides information about community expectations and ordinances that deal with maintenance, vehicle parking and other issues. Peterson said second- and third-generation immigrant families are “making a heck of an effort” to take care of their homes, in turn stabilizing older neighborhoods.

A focus on rehab in St. James

Meanwhile, St. James, a city of 4,500 people in Watonwan County in southwestern Minnesota, will receive $663,000 from the Small Cities initiative. The money will be used to repair 15 homes in the city’s older core, along with three rental units and eight commercial buildings, according to Jamie Scheffer, the city’s economic development director.

In recent years, the city has emphasized the rehabilitation of its existing housing stock rather than focusing solely on new construction, Scheffer said. Like Willmar, it has many newer immigrants; about 35 percent of the city’s population consists of Latinos, many of whom live in the older housing stock.

As a supplement to the home rehabilitation loans, the city also provides homeowners with maintenance and handyman classes, as well as a housing resource guide printed in both English and Spanish.

“A lot of people have moved here from countries that have little to no building codes and lower standards of living,” Scheffer said. “Not only [St. James’s], but Minnesota’s building code is quite intensive and it’s hard to adjust. We are doing what can to take down some of those barriers.”

MinnPost by Gregg Aamot